If you had been vegan in the 19th century, what could you have ordered off a restaurant menu? And how would your options have improved over time? New York Public Library’s historical menu collection can help answer those questions. The collection holds almost 50,000 menus from restaurants and hotels across the United States, about a quarter of which have been digitized and transcribed so the public can browse them online.

“I think menus are fascinating cultural artifacts that help us understand immigration, urban development, [and] food history,” said Rebecca Federman, who has worked with the menus at the library for more than a decade and now manages the collection. “But in a larger context, they can reveal far more.”

As just a few examples, Federman said contemporary chefs have consulted the collection for inspiration, and authors have used it in search of details to include in their works of historical fiction. A marine biologist once searched the menus for clues about changes in wild fish populations.

You’d probably expect to see dramatic changes in vegan cuisine over the last 173 years. With the NYPL menu collection, we can see exactly how and when it evolved.

A hotel’s dinner menu from 1854

Table of Contents

1850 to 1870: Vegan sides and snacks

The collection’s earliest menus didn’t give a lot of detail. Their offerings sound more like a grocery list, with dishes listed plainly, including “oranges, figs, beets, or squash.”

Among the menus from the mid-19th century, none appear to offer a meatless entrée. But if you traveled back in time to this era, you could probably still find enough to fill you up. Choose a basic carb such as boiled rice or dry toast, pair it with vegetables and spreads à la plain celery, radish relish, or plum preserves, top it all off with walnuts for some crunch, and you’ve got yourself a meal, even if slightly incohesive.

Hotel lobby menu from 1881

Hotel lobby menu from 1881

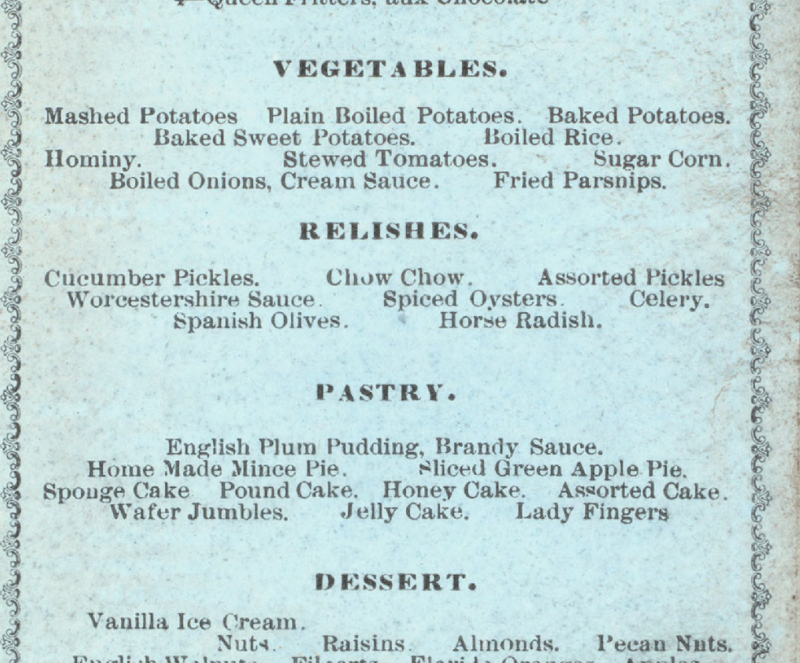

1870 to 1900: There’s always salad

Menus from the late 19th century still offered plenty of hot vegetable side dishes, but it seems like more interest in salads and relishes (cold vegetables) emerged during this time. Chicory and cucumber salad would have been refreshing on a summer day, or if you really wanted to cool off, you might go with frozen tomatoes and lettuce.

Also during this time, reigning supreme among sides were potatoes—which to this day are still a vegan’s best friend at a non-vegan restaurant. Plain potatoes were prepared in every form imaginable, including fried, griddled, mashed, boiled, and ribboned.

Dairy-free frozen desserts were also common during this time. Vegans could have treated themselves to sorbet aux groseilles (currants) or young America sorbet (the jury is still out on what this is exactly, so best to ask the waiter if this flavor ever reappears on a menu).

Pure Food Ca

Pure Food Ca

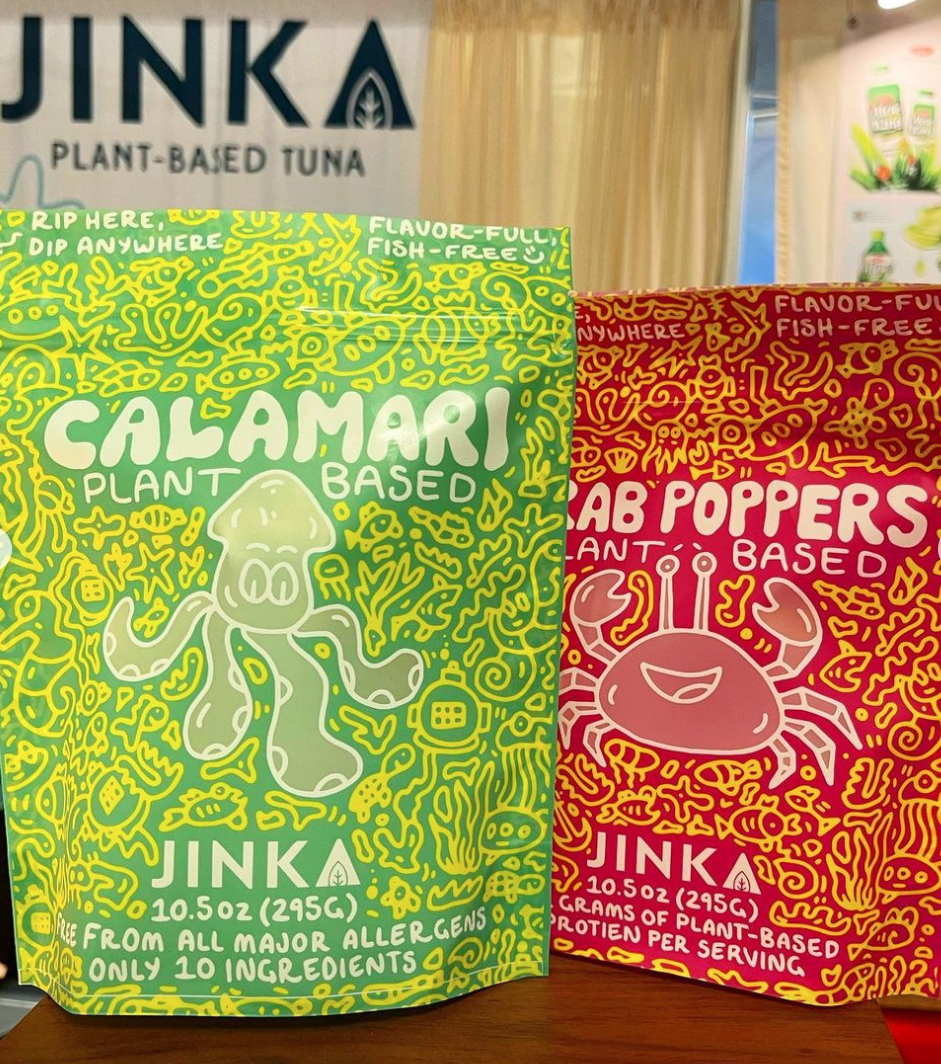

1900 to 1950: The dawn of plant-based meats

Among the library’s menus that have been digitized so far, the word “vegetarian” first appeared in 1900 on the menu of a Chicago restaurant called Pure Food Cafe. The restaurant’s name was in reference to the pure food movement of the time, which raised awareness of the scandals in the meat industry. It’s uncertain which dishes would have contained dairy or eggs at Pure Food Cafe, but it’s clear that none of them contained meat. The breaded mock chicken and vegetarian meat sandwich are particularly intriguing.

Vegetable set plates became somewhat common when meat was rationed during World War II. Wartime lunch counters around the country listed options such as a Vegetarian Platter with fried tomato and Fresh Vegetable Plate. Let’s not forget this was also the time of the Depression Cake—also known as Crazy Cake or Wacky Cake—which is an accidentally vegan cake invented in the 1940s when commodities such as eggs and butter were rationed.

Xochitl

Xochitl

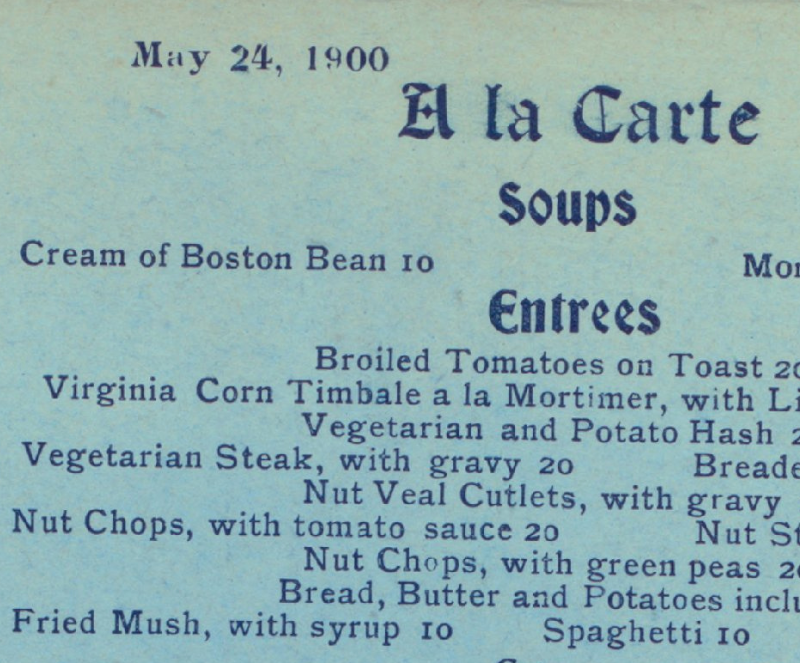

1950 to 1970: Going global

The overall menu collection shows a heavy reliance on English, French, and German cuisine since the earliest years on record, but broader diversity had become commonplace by the mid-20th century.

At the Italian American restaurants that were popular by this time, vegan diners could have chosen vermicelli in scarpara sauce or a host of other kinds of pasta in tomato-based sauces. Kosher restaurants were often meatless, and though many dishes contained dairy, there were likely to be at least a few that were free of animal products.

The avocado—a mainstay of today’s vegan lifestyle—made its debut on the menus of this era. Various eateries served them in an avocado sandwich; romaine, grapefruit, and avocado salad; and as their own side dish—halved avocado with fruit salad.

Zen Palate

Zen Palate

1970 to 2010: The great American tofu boom

Finally, by the late 20th and early 21st centuries, there was a breakthrough. One could almost expect to find a few intentionally vegan options at most restaurants, at least in bigger cities. And particularly at restaurants serving food influenced by Asian cuisines.

Among the digitized menus, tofu’s first appearance is on a 1984 menu from a Thai-American restaurant in Minneapolis called The King and I which is still in operation today. In its earliest days, The King and I served fried tofu with sweet and sour sauce, mock duck and vegetable stir fry, and vegetarian curry with creamy coconut milk.

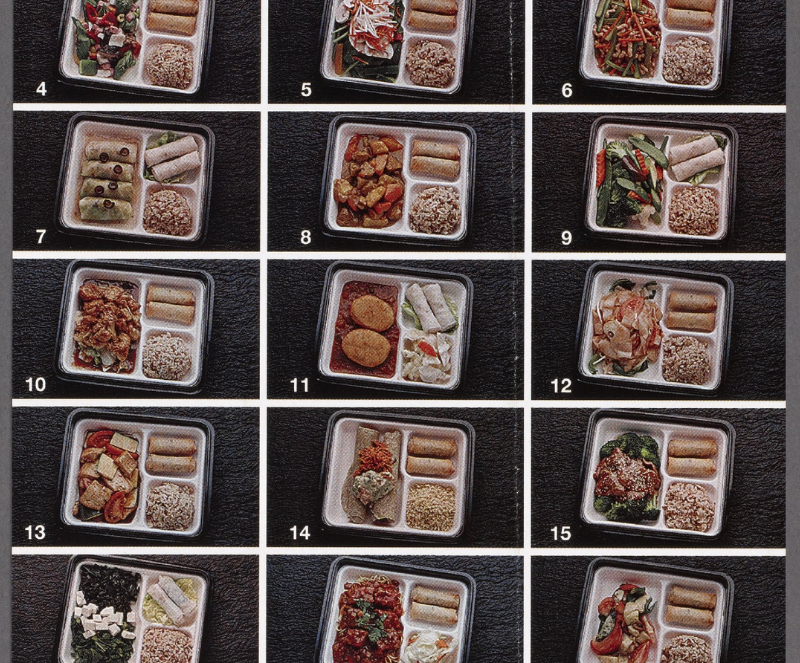

Sushi restaurants like Genroku Sushi in New York served kappa-maki (a basic cucumber roll) and oshinko (pickled radish roll). Chinese-American restaurants usually had numerous vegetable-based dishes that dialed up the umami with soy sauce instead of meat, such as black mushroom with green kale, bean curds with snow peas, and vegetarian sauté.

The number of entirely vegan restaurants started to climb in the 1990s. For example, Zen Palate in Westbury, NY, served complex, contemporary dishes such as Shredded Melody—shredded soy gluten sautéed with celery, carrots, zucchini, and pine nuts in a spicy-sweet sauce with taro spring rolls and brown rice.

During these years, other American restaurants honed the dishes that have become some of the staples of our time, like veggie burgers, veggie lasagnas, and meatless chilis. While not included in these archives, Canoga Park, CA’s Follow Your Heart Market & Cafe started cranking out its famed Avocado, Tomato, and Sprouts sandwich among other vegan-friendly items since 1970.

Screamer’s Pizzeria

Screamer’s Pizzeria

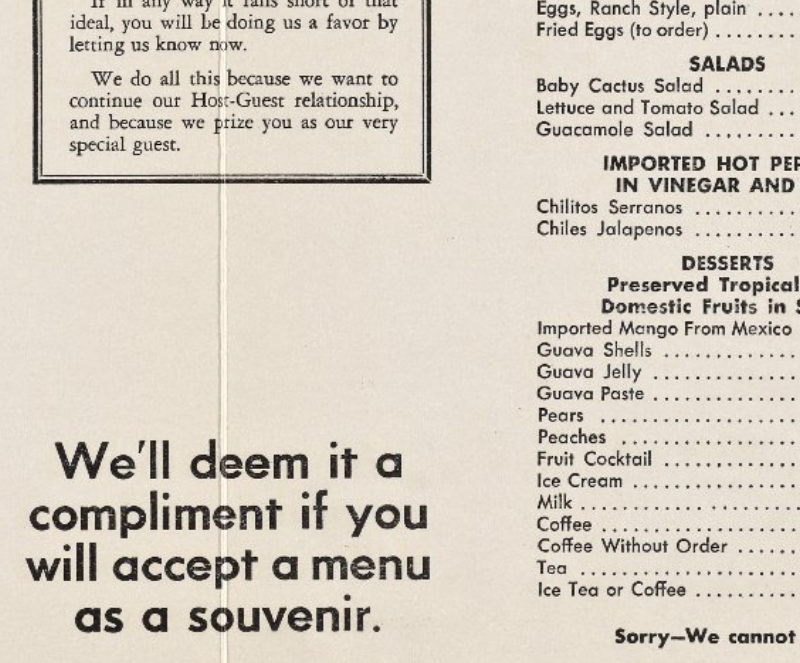

2010 to today: Endless possibilities

The defining shift of vegan dining is the emergence of completely vegan restaurants, dedicated vegan menus, and the increased abundance of plant-based alternatives that can be found in both vegan and non-vegan establishments.

Pizza is one of the most progressive concepts to have adopted vegan options. Going vegan no longer mandates giving up this favorite food, as vegan cheese and even plant-based meats have found their way onto independent and chain pizzerias. “There’s no excuse anymore,” said Joy Strang, executive chef at Screamer’s Pizzeria, which won the 2023 VegNews Veggie Award for Best Vegan Pizzeria.

“We’ve come so far that you can be vegan and still enjoy everything you wanted to enjoy, including pizza,” she said.

Strang remembers the mid-2010s in New York when vegans would no longer accept cheese-less crust with vegetables as proper pizza. The demand for better toppings and plant-based cheese led to the birth of Screamer’s in Brooklyn. With house-made almond ricotta, seitan sausage, buffalo cauliflower, and an array of other reimagined toppings, Screamer’s supplies a hopeful outlook for the next era of American pizzerias.

Raven’s Restaurant

Raven’s Restaurant

Over on the West Coast, The Ravens Restaurant at The Stanford Inn by the Sea in Mendocino, CA elevates vegan cuisine to a sophisticated, fine-dining experience. Many of the ingredients are organically grown in a garden on-site.

Celebrity chef Matthew Kenney has also been a pioneer in vegan fine dining, launching chic plant-based restaurants worldwide. Even omnivorous restaurants have come to the light, as evident by Eleven Madison Park’s shocking yet celebrated shift to transform its omnivorous tasting menu to a completely vegan one.

Vegan dining has come a long way from frozen tomatoes with lettuce, and it’s evolving at a rapid pace. We can’t wait to see (and taste) what the next few decades will bring.