In Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, published in 1905, a young man called Jurgis Rudkis immigrates to Chicago from Lithuania. He’s excited about his new life, he marries, uses credit to buy a house, and gets a job in a local meat packing firm. But soon he learns the grim reality of shoveling animal guts for a living. Workers are exploited, pushed to work all the hours under the sun and paid the bare minimum, and struggle with diseases and injuries in unsanitary conditions. Rudkis himself was fictional, but his experiences were real, based on Sinclair’s own observations of the meat industry. And unfortunately, they’re not exclusive to the meatpacking world that existed in the 1900s. Today, the meat industry is not just associated with environmental and animal rights issues, but it’s rife with human rights abuses, too.

Table of Contents

The meat industry’s history

Research suggests that humans and our ancestors have eaten meat for millions of years. And butchers have likely been around for centuries (evidence of the first-known butcher shop was found in Devon, in the UK, and dates back 1,700 years). But it wasn’t until the mid-1600s that the industrialized meat industry we know today had its start.

William Pynchon, an English colonist and fur trader, opened the first meatpacking facility, which loaded pork into barrels for export, in Massachusetts in 1662. And about 80 years later, the first meat auction in the colonies was held near Boston, reports Stacker Media.

Over the years, cattle drives started to take place, and in the early 1800s, Cincinnati, OH became home to the first large-scale pork-packing plant (the city eventually became a pork-producing hub and was even dubbed “Porkopolis”). Meat started to soar in popularity and the demand was so high, small-scale family farms just couldn’t keep up. This paved the way for cattle barons (otherwise known as rich men who controlled most of the cattle industry in the 19th century) to open huge ranches and dominate the market.

By the 1860s, the great “railroad revolution” was well underway in the US, and it was easier than ever to transport cattle around the country. In the 1870s, the development of refrigerated carts meant that already-processed meat could be transported, too. And by this point, meatpacking plants had also become more streamlined, with sophisticated technology, mechanical choppers, and assembly lines. Oscar Mayer, which is still a big meat company in the US to this day, opened in the early 1880s, and by then, the modern meat industry that we know now was starting to take shape.

Unsplash

Modern meat industry

Today, centralization is king in the meat industry. The days of most people eating meat from small local farms are long gone. And now, a very small number of large corporations produce the majority of meat that arrives in grocery store aisles. In the US, meat giants like Cargill, Tyson Foods, JBS, and Marfrig, each of which is worth billions, control most of the market.

Every year, the meat industry raises and slaughters billions of animals, including cows, sheep, pigs, chickens, and turkeys. All of this comes with a major environmental impact; livestock emits 14.5 percent of emissions, drives deforestation, and pollutes the air and valuable water systems, putting the health of local communities at risk. But still, the meat industry grows. Right now, the US meat industry alone is worth more than $165 billion. Globally, the value is nearly $900 billion. And by 2027, Statia predicts that the global market could hit a value of more than $1 trillion.

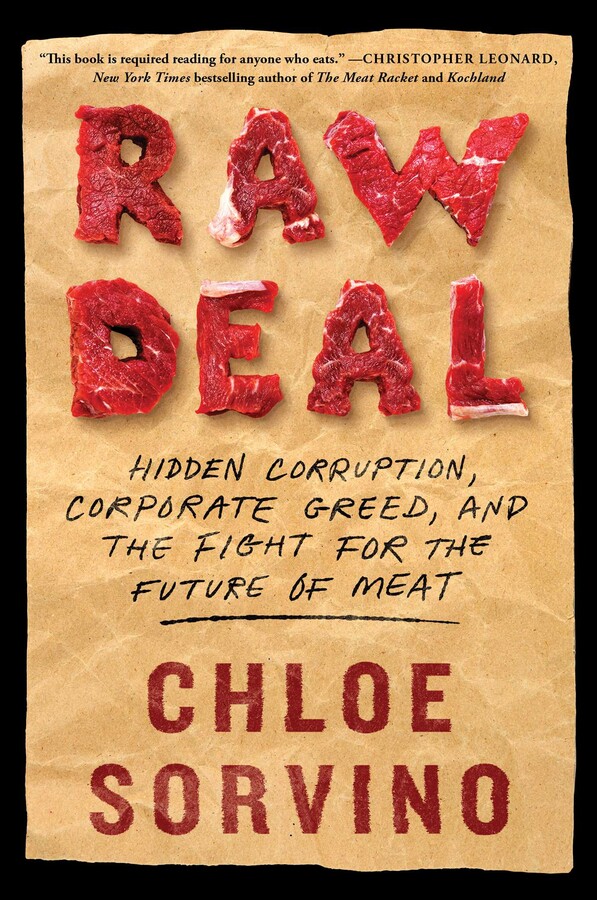

But aside from animals, the planet, and human health, there’s another, major problem with the way the meat industry operates: it routinely and systemically exploits and abuses human beings in its own supply chains. Sinclair’s fictional account was harrowing, but the truth is even worse, reports Chloe Sorvino, a journalist for Forbes and author of the book Raw Deal: Hidden Corruption, Corporate Greed, and the Fight for the Future of Meat.

Simon and Schuster

Simon and Schuster

Human rights violations in the meat industry

Sorvino was awakened to the harsh realities of the meat industry while she was working “the billionaires beat” at Forbes. It was after interviewing the big dogs of the meat industry that she started to realize the extent of the “wealth and consolidation of power” in the market. The folks at the top get richer and richer, while the vulnerable workers on the meatpacking assembly lines get paid less and less, and exploited more and more.

Like Sinclair’s Rudkis, most are immigrants. “It’s a tale as old as time,” Sorvino told VegNews. “The Jungle was a novel, but it was based on the reporting that Sinclair did in these slaughterhouses. Even back then, there were many, many immigrants working in the slaughterhouses. It’s because it’s a dirty, dangerous job, seen by some as unseemly. That’s why the industry has made a point of working with immigrants or seeking out refugees or other workers who may not have very many other places to work.”

During her research for Raw Deal, Sorvino sifted through hundreds and hundreds of lawsuits and class actions, filed by desperate workers trying to get justice for the way they’d been treated by the industry’s biggest corporations. But JBS, she says, was among the worst. “The ‘Human Cost of Eating Meat’ chapter in my book is all from cases at JBS plants, and we did that intentionally,” she says. “There have been a lot of human rights violations, different abuse allegations, discrimination allegations that have come up across the history of the industry. But JBS, there are so many different examples.”

She recalls one case, in particular, in which a pregnant worker for Pilgrim’s Pride, which JBS owns, had to ask to go to the bathroom. “That was often used as a way to exert control and power,” says Sorvino. The worker also wasn’t allowed to change to a job that involved less standing, despite recommendations from her doctor. “She ended up miscarrying,” recalls Sorvino.

Another separate lawsuit refers to one worker who complained about religious discrimination during her job at one unnamed meat plant. She was pushed further and further down the assembly line, experiencing different injuries, before she ended up working in the “gut bin,” which, as the name suggests, is where all the carcasses, oils, manure, sewage, and more undesirables end up. She ended up having a psychological breakdown, says Sorvino. “These stories hit at every level of dignity and human experience,” she notes. “They can just be really shaking.”

But she’s eager to note that while there are, of course, some cases of “really bad actors in these plants,” the problem is systemic. And the pandemic shone a light on just how deep it runs. There were outbreaks in meat plants all over the world, likely due to the close proximity of working conditions, many speculated, but also because of poor employment contracts. Sorvino says workers were being forced onto lines to keep the meat supply going, despite the fact they may have been sick themselves or had sick family members.

Since then, multiple reports have helped to paint a picture of just how exploitative and abusive the global meat industry can be towards human beings.

In 2021, one investigation by the Guardian found that meat companies in Europe had been hiring thousands of workers (many of them migrants) through subcontractors and agencies, and then subjecting them to “inferior pay and conditions.” And in 2022, a worker called Montserrat Castañé filed a landmark legal challenge, alleging she and others had suffered sexual abuse in a Spanish abattoir. She lost the challenge, but pledged to continue “fighting harassment against women both in the courts and in the streets.” In the same year, JBS was accused of using child labor in a meatpacking plant in Nebraska.

“The workers at these plants are among the most vulnerable in America, and they are working some of the most dangerous jobs in America,” says Sorvino. “And not only have they been historically really low paid over the decades, but there have been even schemes, especially in the chicken industry, to subjugate these workers and to manipulate their wages and their benefits and their healthcare so they are as low and as cheap as possible.”

Unsplash

Unsplash

Can we hold the meat industry accountable?

Ultimately, lawsuits are not enough to change the meat industry. The market is run on exploitation, and yet, it still turns billions in profit every year, unaffected by most legal challenges or settlements. This is mostly because it’s hidden away, which makes it easy for the average meat consumer to make their purchase without thinking about the human cost. “Americans have no idea where their meat comes from,” Sorvino says. “That’s hurting us, and it’s also making others rich and it’s hurting so many of these workers.”

One solution, according to Sorvino, is to peel back the foundations of how we produce food. We need to embrace a plant-forward system for the animals and the planet, but food production, in general, also needs to get smaller, moving back into local communities. Essentially, we shouldn’t allow the growing plant-based meat industry to start mimicking the set-up of Big Meat, where a few companies reign supreme.

“There’s a need for more infrastructure on the regional level,” she explains. “There’s been a gutting in the US of local plants, local canneries, different types of systems that used to be there that just went away as big corporations centralized.”

Doing this will not only help to shape a fairer, more ethical food industry for its workers, but it will also help with so many other issues, like accessibility and food insecurity. Right now, more than 23 million people live in food deserts in the US, where access to healthy, affordable foods, like fruits and vegetables and other plant-based ingredients, is limited, and fast-food chains, where menus are largely dominated with meat products, are common.

“We need to have community-based systems,” Sorvino says. “Different organizations, patchwork layers on top of each other, working to have a more regionalized food system.” But, she’s also keen to note that while individuals can make a small amount of difference, she’s not about pushing guilt. The real change has to start from the top down. “Voting with your dollars isn’t completely meaningless,” she adds. “But at the end of the day, the individual choice has no ability to counterbalance the dollar from a billionaire.”